Understanding CMT Through Mechanism, Not Just Diagnosis

📌 Series Introduction

In an era where AI-based variant interpretation tools have become widely adopted, this series focuses on what human interpreters must still understand and decide after automated prioritization.

Each episode centers on a specific disease group, examining genetic mechanisms and clinical spectra together, with the goal of moving beyond simply “finding variants” toward explaining and interpreting them in a clinically meaningful way.

Episode 1 — Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease (CMT)

Why CMT comes the First Disease

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) is one of the most common inherited peripheral neuropathies.

However, despite its frequency, it is also one of the disease groups that generates the most confusion and misinterpretation in clinical variant analysis.

Although CMT is referred to as a single disease entity, it encompasses multiple genes, diverse phenotypes, and heterogeneous clinical courses.

For this reason, CMT serves as a representative example of why genetic disorders should be understood not simply by their “name,” but through a broader and deeper perspective centered on the mechanisms that drive them.

What Is Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease?

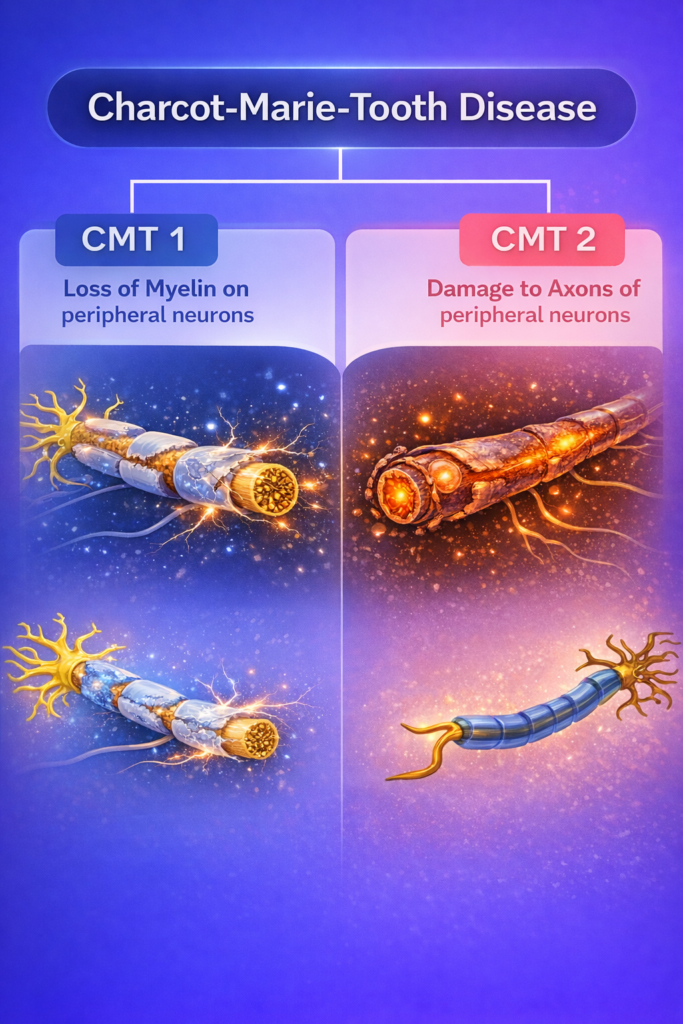

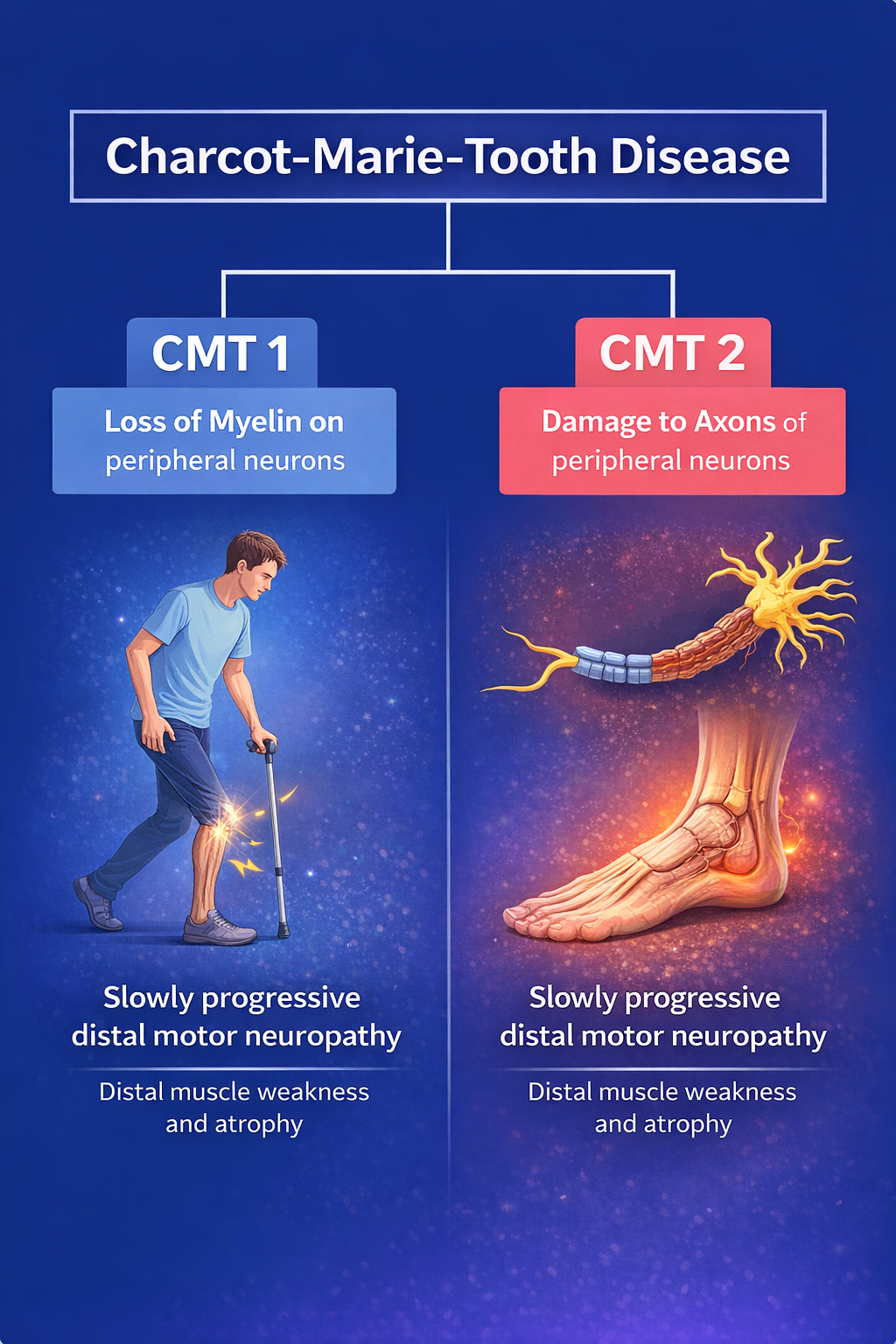

CMT is the most common inherited peripheral neuropathy, caused by abnormalities in either the myelin sheath or the axon of peripheral nerves.

These abnormalities lead to progressive motor weakness and sensory impairment.

Clinically, symptoms typically begin in the **distal** muscles of the arms and legs.

As the disease progresses, muscle atrophy, gait disturbance, and sensory loss become more prominent.

Key Clinical Features of CMT

- Slowly progressive distal motor neuropathy

- Distal muscle weakness and atrophy

- Pes cavus deformity

- Reduced or absent tendon reflexes

- Age of onset: typically 10–30 years (but may range from infancy to late adulthood)

- Prevalence: approximately 1 in 2,500

- Primary system involved: Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

The Starting Point for Understanding CMT: Peripheral Nerve Structure

Peripheral nerves consist of two main components.

The axon transmits neural signals, while the surrounding myelin sheath enables rapid signal conduction through saltatory conduction.

CMT can be broadly divided based on which of these structures is primarily affected:

- disorders of the myelin sheath, and

- disorders of the axon itself.

This distinction is not merely classificatory—it fundamentally shapes both disease mechanism and interpretation strategy.

Interpreting these clinical features requires an understanding of the structural components of the peripheral nerve from which they originate.

Demyelinating CMT vs Axonal CMT

Demyelinating CMT

- Failure of myelin structure or maintenance

- Markedly reduced nerve conduction velocity (NCV)

- Possible nerve enlargement

Axonal CMT

- Structural or functional damage to the axon

- NCV relatively preserved, but reduced amplitude

- Length-dependent nerve damage

Because clinical symptoms alone cannot reliably distinguish these subtypes, electrophysiological data (NCV and amplitude) play a critical role in interpretation.

Key Genes and Mechanisms in CMT Interpretation

Although dozens of genes are associated with CMT, from an interpretation standpoint it is more useful to focus on representative genes that illustrate distinct pathophysiological mechanisms.

1) PMP22 — A classic example of demyelinating Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease

PMP22 is the hallmark gene of demyelinating CMT.

It encodes a myelin protein expressed in Schwann cells and is essential for myelin formation and stability.

A defining feature of PMP22 is that its pathogenic mechanism depends strongly on variant type and gene dosage.

Duplication

- PMP22 overexpression

- Proteasome overload

- Intracellular aggregates

- Impaired Schwann cell maturation

- Classic CMT1A

Point mutation

- Failure of protein trafficking to the cell membrane

- Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress

- Demyelination

Deletion

- Myelin instability

- Increased susceptibility to pressure palsies

- Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP)

For PMP22, interpretation goes beyond the presence of a variant; it requires considering the variant type (e.g., dosage alterations versus point mutations) and the molecular disease mechanism it drives.

2) MPZ & SH3TC2 — Myelin Structural Integrity and Maintenance Failure

In demyelinating CMT, MPZ and SH3TC2 must be considered alongside PMP22.

These genes affect not the quantity of myelin, but its structural integrity and maintenance.

MPZ — A Core Structural Myelin Protein

MPZ (Myelin Protein Zero, P0) accounts for approximately 50% of peripheral myelin protein.

It maintains adhesion between myelin lamellae.

Pathogenic variants lead to:

- Failure of myelin adhesion

- Structural collapse of the myelin sheath

- Demyelination

Accordingly, interpretation of MPZ-related CMT should focus on the underlying mechanism of myelin structural collapse rather than demyelination alone.

3) SH3TC2 — A protein required for the formation of the node of Ranvier

SH3TC2 is involved in endosomal recycling and regulation of myelination, and is closely linked to the NRG1/ErbB signaling pathway.

Pathogenic mechanism:

- Disruption of NRG1/ErbB signaling

- Hypomyelination

- Repeated demyelination–remyelination

- Onion bulb formation

Although MPZ and SH3TC2 are both classified as demyelinating CMT genes,

their mechanisms are fundamentally different.

4) GJB1 — Gap Junction Dysfunction and CNS Involvement

GJB1 encodes the Connexin 32 protein, which forms gap junctions and helps maintain metabolic coupling between Schwann cells and axons.

Because it is also expressed in oligodendrocytes, GJB1 is one of the rare CMT-associated genes that can be accompanied by central nervous system involvement.

Loss of function

- Impaired formation of functional channels

- Failure to traffic to the cell surface

- Loss of gap junction function

- Myelin disruption

- Secondary axonal degeneration

Gain of function

- Defective hemichannel pairing

- Resulting in abnormal ion permeability

- Leading to impaired intracellular ion balance

- More pronounced neuronal injury

- Potential CNS manifestations

When interpreting GJB1 variants, both peripheral and central nervous system features should be considered.

5) MFN2 and GDAP1 — Axonal CMT and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

MFN2 is a representative gene for axonal CMT.

It plays a key role in mitochondrial fusion and network maintenance, which is critical for energy supply in long peripheral axons.

Pathogenic mechanism:

- Impaired mitochondrial fusion

- Disrupted ER–mitochondria interaction

- Failure of distal axonal energy supply

GDAP1 encodes ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated protein 1.

It is located in the outer mitochondrial membrane and plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial fusion and fission dynamics.

Pathogenic mechanism:

- Disruption of the balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission

- Leading to abnormal mitochondrial distribution and impaired mitochondrial function

Characteristic clinical features: In patients with GDAP1-related CMT, highly distinctive symptoms may be observed, including:

- Vocal cord paralysis

- hoarseness

MFN2-related CMT often shows relatively preserved NCV with markedly reduced amplitude, and may be accompanied by extended phenotypes such as optic atrophy and hearing loss.

GDAP1-related CMT is also characterized by relatively preserved nerve conduction velocity, while a marked reduction in amplitude is often observed.

In addition, distinctive clinical features such as vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness may be present.

6) HINT1 — A metabolic axonal neuropathy caused by defects in mRNA processing

HINT1 functions as a purine phosphoramidase enzyme and operates in a homodimeric form.

It is not merely a simple metabolic enzyme; HINT1 also participates in the regulation of transcription factor activity and mRNA processing pathways.

In addition, it interacts with the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), contributing to the modulation of pain and sensory signaling.

Pathogenic mechanism

- Defects in the enzyme active site

- Protein instability and nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)

- Impaired dimerization

- Disruption of the mRNA processing pathway

- Metabolic imbalance leading to axonal degeneration

HINT1 exemplifies why functional gene labels alone are insufficient, and why mechanism-based interpretation is essential.

7) SORD — Metabolic Axonal Neuropathy and an NGS Pitfall

SORD encodes a key enzyme in the polyol pathway, converting glucose to sorbitol and fructose.

Pathogenic mechanism:

- Sorbitol accumulation

- Osmotic and oxidative stress

- NADPH depletion

- Axonal damage

SORD requires particular caution in NGS interpretation:

- Presence of the SORD2P pseudogene (~90% sequence similarity)

- The common pathogenic variant **c.757delG** is normal in the pseudogene

Therefore, coverage and read alignment must be carefully reviewed.

CMT Is Not Limited to Peripheral Neuropathy

Depending on the gene involved, CMT may present with systemic features beyond peripheral neuropathy:

- Optic atrophy (MFN2)

- Hearing loss (PMP22, GJB1)

- Vocal cord paralysis (GDAP1)

- Neuromyotonia (HINT1)

- Cognitive decline (MFN2, MCM3AP)

This further underscores the importance of comprehensive phenotype integration.

Common Misconceptions in CMT Interpretation (Top 5)

1️⃣ CMT is a single disease

2️⃣ Clinical features alone can define the subtype

3️⃣ CMT affects only peripheral nerves

4️⃣ A pathogenic variant automatically establishes diagnosis

5️⃣ High AI prioritization equals causative relevance

All of these stem from insufficient mechanism-based interpretation.

Additional Practical Considerations in CMT Interpretation

1️⃣ Always consider CNVs together with SNVs

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) is a disorder in which copy number variants (CNVs) are very frequently causative, in addition to single nucleotide variants (SNVs).

- PMP22 duplication/deletion is one of the most common causes encountered in CMT interpretation.

- An SNV-focused analysis alone can easily miss classic CMT1A or HNPP cases.

👉 When interpreting WES/WGS data, CNV caller results must always be reviewed in parallel.

2️⃣ Do not fix the inheritance mode too early

CMT can follow autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), or X-linked inheritance.

- Although many cases are initially assumed to be AD based on limited clinical information, AR-CMT and X-linked CMT (e.g., GJB1) are also common.

👉 Restricting the inheritance model too early in the interpretation process can artificially narrow the candidate variant space and lead to missed diagnoses.

3️⃣ Avoid oversimplifying early-onset vs late-onset disease

Traditionally, CMT has been classified as:

- early-onset → demyelinating

- late-onset → axonal

However, real-world clinical practice shows many exceptions, such as:

- Early-onset axonal CMT due to MFN2

- Late-onset demyelinating CMT due to MPZ

👉 Age at onset is contextual information, not a definitive criterion for subtype classification.

4️⃣ Interpret electrophysiology results quantitatively

Describing nerve conduction studies simply as “decreased” can obscure important mechanistic clues.

- NCV < 38 m/s → strong suggestion of a demyelinating process

- Reduced amplitude with preserved NCV → more consistent with an axonal process

👉 Quantitative interpretation allows clearer linkage between genes and disease mechanisms.

5️⃣ Intentionally keep phenotype expansion open

Although CMT often presents as a pure peripheral neuropathy, phenotypic expansion should be deliberately considered during interpretation.

Examples include:

- Optic atrophy → MFN2

- Vocal cord paralysis → GDAP1

- Transient CNS symptoms → GJB1

- Neuromyotonia → HINT1

👉 An overly narrow initial HPO set can exclude the true causal gene.

6️⃣ Consider “CMT-like phenotypes”

Not all peripheral neuropathies are CMT.

Differential diagnoses include:

- Hereditary sensory neuropathy

- Distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN)

- Mitochondrial disease

- Metabolic neuropathy

👉 When a CMT panel is negative, neuropathies driven by alternative mechanisms should also be actively considered.

7️⃣ A negative result is still informative

In CMT, there remain:

- Cases with unknown causative genes

- Cases caused by structural or atypical variants

👉 A “negative” result is not a failure, but valuable information that guides the next step—such as WGS, reanalysis, or long-read sequencing.

Final Message: What CMT Teaches Us About Interpretation

CMT clearly demonstrates that gene ≠ diagnosis and variant ≠ causative.

Accurate interpretation requires understanding which level of peripheral nerve biology is disrupted, not simply identifying a gene name.

This is why, even in the AI era, the role of the human interpreter remains indispensable.

답글 남기기

댓글을 달기 위해서는 로그인해야합니다.